“We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces!” the aged movie star exclaims in Sunset Boulevard.

Long before Jigsaw and Annabelle, Ghostface and Samara—going back to even before Freddy and Jason—there were the Universal Monsters. These were the creatures and character designs who were so iconic that they defined what the horror genre was to most moviegoers during the earliest decades of talking pictures. Primarily released in two film cycles by Universal Pictures across the 1930s and ‘40s (plus a few outliers on both sides of this), the legacy of these films and the people who made them endures still. It echoes in Halloween costumes and TV specials, merchandise toys and candies, it’s even informing recent Blumhouse films and Netflix’s Wednesday.

Yet to return to the original movement of films which were so frightening in their day that they essentially invented the horror genre in the U.S., we are left with a collection of classic chillers… and a lot of sequels that are sometimes still a lot of fun. But which are the best and which are best left to molder in their cobwebbed crypts? We’ve gone back and revisited all of the mainline Universal Monsters films* to figure that out for your shrieking pleasure.

So, in their way, did Hollywood’s great movie studios, each of which had its distinctive attributes. MGM boasted of “more stars than there are in the heavens,” Paramount cultivated a European sophistication, Warner specialized in urban tough guys. And Universal had monsters.

Universal Classic Monsters: Complete 30-Film Collection 1931-1956, which was released a decade ago and includes one bonus feature film (the estimable Spanish-language version of Dracula), offers a bountiful sampling of the studio’s signature product, organized by character to include such deathless creations as Dracula, Frankenstein, the Mummy, the Invisible Man and, the Wolf Man.

Universal staked a claim to horror films during the silent era with two Lone Chaney vehicles, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925):

but it was the phenomenal success of talkie Dracula (1931) that righted the Depression-rocked studio's course. There were hopes that Chaney would take the title role in a movie made by his frequent director Tod Browning, but the star's fatal illness necessitated finding a replacement:

Bela Lugosi, the Hungarian actor who played the vampire count on the Broadway stage. The substitution was fortuitous. Lugosi's "demented poetry and total conviction," as the film historian Carlos Clarens put it, redeemed an otherwise turgid and pedestrian movie.

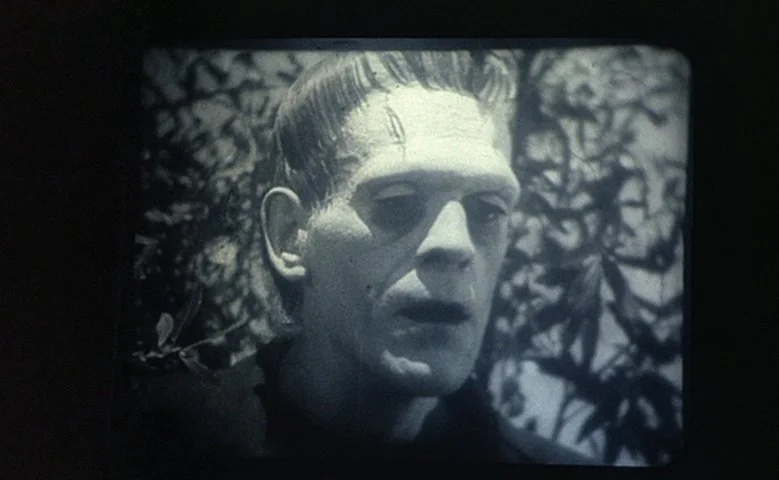

Lugosi, however, was too vain to play the monster in Universal's follow-up horror movie, Frankenstein (1931), thus opening the door for the British actor Boris Karloff, whose fusion with Jack P. Pierce's makeup made him the eternal visage of Hollywood horror.

Directed by James Whale, Frankenstein is far better filmmaking than Dracula and was comparatively remunerative.

New monsters were born.

Karl Freund, the German-born cameraman who shot Dracula, directed an atmospheric Egyptian variant, The Mummy (1932), with an impressively wrinkled Karloff popping out of a sarcophagus to terrorize a team of heedless archaeologists. Whale made The Invisible Man (1933), introducing Claude Rains in a role Karloff declined, as the movie's megalomaniacal if all but unseen protagonist.

Dracula and Frankenstein resurrected Universal; the success of the The Invisible Man returned the studio to profitability. Remarkably fresh after 91 years, the movie is a sly, riotous special-effects comedy accentuating the dark humor that, already present in Frankenstein, would fully blossom in Bride of Frankenstein.

The meeting if not quite the mating of Karloff's creature and Elsa Lanchester's bride — crowned with a frizzy electric-shock coiffure and moving like a robot ballerina to Franz Waxman's surging score — is not only the climax of the movie but also the high point of Universal monsterdom.

These selected films have and continue to excite audiences around the world.

So much the one of which Frankenstein inspired the creation of today's focused discussion; which takes us out of the Hollywood system and transports us to Spain.

The Spirit of the Beehive

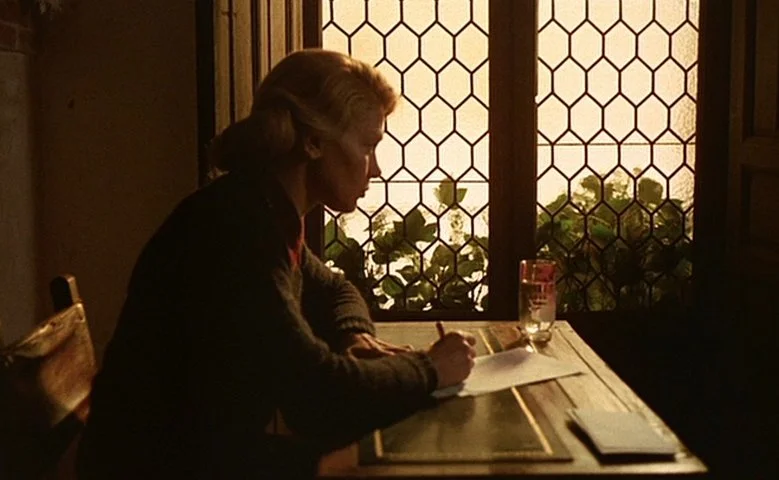

Víctor Erice's spellbinding The Spirit of the Beehive (El espíritu de la colmena), widely regarded as the greatest Spanish film of the 1970s. In a small Castilian village in 1940, in the wake of the country's devastating civil war, six-year-old Ana attends a traveling movie show of Frankenstein and becomes possessed by the memory of it. Produced as Franco's long regime was nearing its end, The Spirit of the Beehive is a bewitching portrait of a child's haunted inner life and one of the most visually arresting movies ever made.

Dictators love the movies. Francisco Franco of Spain was no exception. The propaganda picture Raza (1942), is even based on a novel written by Franco.

Subtlety, however, often jams the radar of even the most suspicious despot, which may explain how the ghostly parable The Spirit Of The Beehive made it into theaters in 1973, at the tail end of Franco's regime. Set in 1940, the film is a condemnation and an elegy, a lament for Spain after the Civil War that brought Franco to power. It's also a deeply moving tribute to the eager inquisitiveness of children and the magic of movies.

Early on, the residents of the Castilian village of Hoyuelos assemble a makeshift cinema out of a war-scarred auditorium. The entire town, it seems, convenes for a screening of James Whale's Frankenstein, its reels delivered by a rickety military-style transport truck, with children from the town leading the way, chanting, "The movie's coming! The movie's coming!"

At the screening, the front rows are occupied by restless, gaping children, one of whom, Ana played unforgettably by Ana Torrent, only 7 years old at the time of filming stares with fascination at the monster up onscreen as it interacts with a girl her own age, picking daisies by a lake. In supplementary interview footage, director Víctor Erice reveals that Torrent was filmed seeing Frankenstein in real time, for the first time, the astonished look on her face a flash of unplanned, unrehearsed documentary filmmaking.

After the screening, Ana becomes obsessed and hounds her older sister Isabel (Isabel Tellería), in an exchange of eerie whispers, about the "the monster." just to get her to bed, Isabel tells Ana: "Everything in the movies is fake. It's all a trick." Isabel then claims Frankenstein was not killed and that she has seen the monster alive in a nearby village.

Accordingly, Ana embarks on a secret search in which she stumbles across a wounded soldier presumably AWOL from the frontlines, hiding out in an abandoned building surrounded by a bleak, brown landscape. Ana returns with food—cautious and suspicious, as if this might actually be the monster. What follows is scene after scene of breathtaking beauty that any student of cinematography should decode and steal from freely. There are bees, magic mushrooms, slow motion, and a Frankenstein cameo that almost ended up on the cutting room floor. The enduring mystique of The Spirit Of The Beehive, now 52 years old, seems to have spread beyond the frame lines. Victor Erice has directed only two features since.

Cinematographer Luis Cuadrado went blind after Beehive wrapped, and he committed suicide seven years later. And even after a slew of other screen appearances, Torrent remains perhaps best known as the young star of this miraculous movie. But is Franco the monster? Five decades removed from its original context, the question no longer seems pressing.

It is one of the strangest stories we have heard of. It concerns one of the great mysteries of creation, life and death. Beware. Perhaps it will offend you. It may even terrify you. Not many films in the whole world have had a greater impact. But I advise you not to take it very seriously.

So says the man in the tuxedo who introduces Frankenstein, the movie within a movie at the beginning of Victor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive, a Spanish movie from 1973. Made in the last years of the Franco era, the plot concerns a young girl, Ana, who lives in a remote town in Spain at the end of the Spanish civil war. After seeing Frankenstein, goaded by her sister, Ana comes to believe that the actual Frankenstein monster lives in an abandoned building outside of town—the same building where a fugitive happens to take refuge. Thus do the girl’s imaginative world and the world of her country’s politics get woven together, until the game of what is real and what is not matters much less than what the filmmaker is able to do by blending the two together.

Those of you who have seen Pan’s Labyrinth or The Devil’s Backbone have probably already noted the many similarities; Guillermo del Toro himself has said that “Spirit of the Beehive is one of those seminal movies that seeped into my very soul.”

But the influence goes far beyond del Toro. My knowledge of Spanish movies is by no means exhaustive, but it seems that Erice’s film is now simply part of Spanish cinema’s DNA. Spirit feels like a blueprint for what I’ve loved about my favorite Spanish movies: the constant sense of the uncanny, the mixing of genres (in Spirit’s case, social documentary, coming-of-age movie, and horror) in a particular way—what kind of movie are we watching again?—and most of all, a plot that starts off kind of weird, gets weirder, gets really weird, and then stops, because the movie isn’t as concerned with wrapping up character and story arcs as it is with chasing the ideas it has as far as it can. Spain seems to be able to churn out movie after movie of the sort that Hollywood doesn’t have the guts to make.

Which is all the more impressive because Spirit of the Beehive is a very quiet movie. Its characters seem to talk only as a last resort, only when the plot can’t be moved forward in any other way. Whenever possible, Spirit moves through images. The isolation of the town is conveyed through absolutely stunning shots of the landscape around it, and the relationships between characters are developed through gestures, glances, or the gift of an apple. It doesn’t ever feel unnatural, but it defies current cinematic conventions, which would almost certainly have had the characters talk more, or filled much of that quiet with a soundtrack, telling us how to feel.

I admit that when I first saw Spirit about a decade ago, I didn’t connect with it at all. It felt like something I was supposed to be watching because I was interested in Spain and Spanish culture, and I was bored. But just last week, when I watched it again, I was hypnotized and shaken. I don’t know what accounts for it. Perhaps my taste has changed. Perhaps I have Guillermo del Toro to thank for breaking me in with Labyrinth and Backbone, making certain elements of Spirit just familiar enough that I could be knocked on my ass by what was unfamiliar. Whatever the case, I can’t seem to get it off my mind. Even sitting at my desk now, the scene where the two girls run across the huge, barren plain to the abandoned house while the clouds throw moving shadows across everything is playing in the back of my head, and I’m amazed all over again at how such a simple scene can be suffused with such wonder and dread. BY BRIAN SLATTERY