The Twilight Zone is a TV series that explores a variety of themes and genres, including science fiction, fantasy, and horror. The show's episodes are standalone stories that often feature characters who experience unusual or disturbing events, and the phrase "twilight zone" has become part of the vernacular to describe surreal experiences. Today we will be analyzing some of the series most standout episodes and the lasting effect the series has had on science fiction for the past 66 years. But first, here's a few tools or ways to analyze the show. But be warned:

You're traveling through another dimension - a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination. That's a signpost up ahead: your next stop: the Twilight Zone!

• Social commentary

The show used madness as a metaphor to critique American society in the late 1950s ano early 1960s. It challenged the idea of uncompromising rationality, social conformity, and the organization of life around work.

• Philosophical inquiry

The show considered questions about the nature of self, the existence of god, the possibility of an afterlife, and more.

• Human nature

Each episode often turns on an essential truth about humanity, such as the cost of pride or judgment, or the destructive nature of paranoia.

• Nostalgia

The show often deals with failure, regret, and loss, and nostalgia informs several

episodes. For example, in the episode Walking Distance, a workaholic advertising executive returns to his hometown and discovers he can't escape the present by retreating into the past.

• Relevance

Some say the show remains relevant today, as many of the issues it explores, such as mental health care and blanket judgments of others, are still relevant

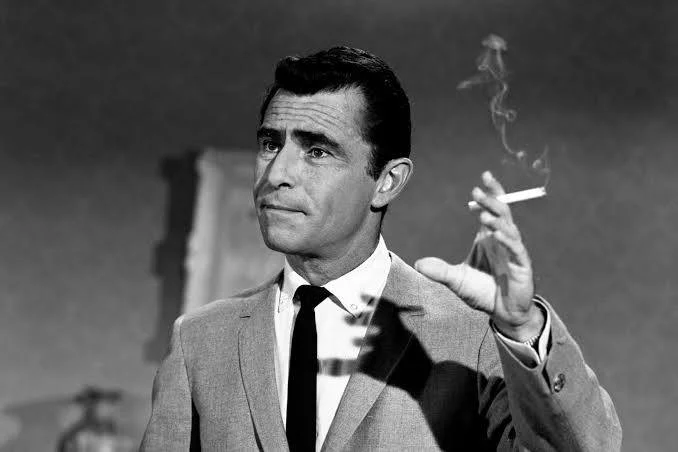

In his 1961 address to the annual convention of the National Association of Broadcasters, Newton Minow famously offered a pessimistic assessment of America's most exciting new industry. Television, declared Minow, was turning into a "vast wasteland" of "blood and thunder" and "formula comedies." Minow, the recently appointed head of the Federal Communications Commission, specified only one weekly series he found "dramatic and moving," a hopeful sign of what broadcast television could become. This was The Twilight Zone, which its creator and chief writer, Rod Serling, described as "a series of imaginative tales that are not bound by time or space or the established laws of nature."

President Barack Obama awards the Presidential Medal of Freedom to former Federal Communications Committee Chairman and Northwestern alumnus Newton Minow during a White House ceremony in 2016. Getty Images

The Twilight Zone won numerous industry awards and wide critical praise during its five-season run from 1959 to 1964 on CBS, confirming Serling's place as one of the most prolific and innovative writers and producers to emerge from the live-drama era of the 1950s, television's original "golden age." But by the time he died in 1975, Serling was probably less well known for his writerly creativity than as the host of a quiz show and as the face of TV commercials for cigarettes and cars.

A man with all the time in the world to read, but his glasses have broken. Amisunderstanding that makes people believe aliens are there to serve them, but in actuality, they plan to eat them. These are stories featured in the quintessential anthology series, The Twilight Zone.

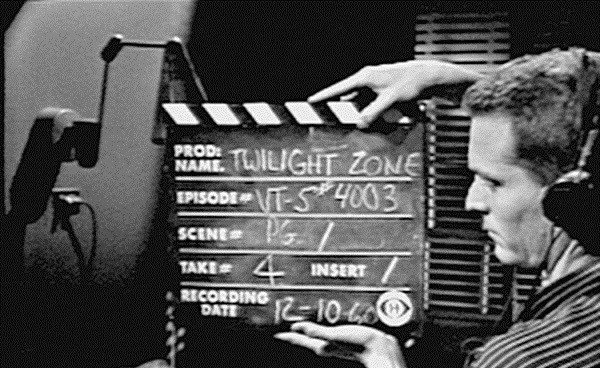

Created and hosted by Rod Serling, The Twilight Zone ran for five seasons and aired 156 episodes from 1959 to 1964. As an anthology series, each week featured a new stand-alone story that would find characters dealing with the strange and unknown.

Simultaneously, Serling was captivating audiences with socially relevant topics that he hoped would change how people viewed the world. He introduced each episode with narration that proclaimed we were entering"the dimension of imagination," and the world of television was forever changed.

Television before The Twilight Zone was all about family programming. Some of the biggest shows of the 1950s, including American Bandstand and I Love Lucy, were breezy entertainment families could enjoy together. That was important because television itself was in its infancy and many homes in the country were lucky to afford one TV for the entire family. That made watching shows on the big three channels (ABC, CBS, and NBC) an important bonding experience.

The shows had to showcase family values and reach a particular standard of decency. Many other television genres including soap operas and game shows all got their start during this period. It wasn't until the 1960s that television became a force for political and social change as TV became a major influence in the Presidential election between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon:

Serling fostered his interest in writing as an editor for his high school paper, and during that time he was a big advocate for Americans enlisting in the war effort — for his part he joined the U.S. Army during World War II, and according to Biography, Serling became a paratrooper and was injured during the war.

The military honored him with a Purple Heart, but combat has a way of changing people and Serling was no different. He turned his attention to the television medium with some fairly ambitious plans. He sought ways to change how people viewed the world they lived in, and he started with his big break on the TV business drama Patterns.

The show was part of the long-running anthology series, Kraft Television Theatre, and Serling won an Emmy for the drama which gave him the clout to tackle other projects. Unlike The Twilight Zone, Patterns has not quite lived on as a [world-renowned piece of filmmaking. It should be, however, for more reasons than one. Sure, its astounding degree of acclaim led to the conceptualization of reruns, but can it still work for audiences in the same way that it did back in the mid-1950s? In short, yes. It does take some patience to get there, though.

Patterns is an unusually emotive story for Rod Serling. It doesn't matter if he's writing a grounded drama or a fantastical science fiction tale, this is a writer whose works typically run the routes of righteous anger and haggard cynicism. While definitely sports some of those traits, it also feels more for its characters than anything you'll find in The Twilight Zone or on a planet of sophisticated apes.

But that clout only extended so far. Serling found it frustrating that his scripts often faced scrutiny. During the 60s, there was a lot of pressure from sponsors who feared their products would be shown in an unflattering light when "difficult" topics were presented to audiences. Difficult topics meant stories that centered on discussions of political and social justice themes.

Serling understood that through the power of television, he could send his messages of social justice to anyone who would tune in. These are the stories he was most interested in writing.

This essay by Hugh A.D. Spencer paints Serling as a man deeply invested in the human rights of all people. He viewed writing and storytelling as a political act, adding that it was the duty of writers to discuss socially significant content in their work.

While often heralded as one of the defining shows of the 1960s, Twilight Zone aired its pilot on October 2nd, 1959. Serling was the center of the show; he wrote 93 of the series' 156 episodes, hosted every episode, and is an essential icon in television history. He has become synonymous with stories about the weird and unusual. Through the lens of science-fiction, Serling could bypass censors and deliver tales of wonder and awe while teaching viewers about the perils of selfishness, racism, and "the inability to respect the rights and integrity of others," words which Serling delivered during his narration for the classic episode "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street."

Twilight Zone struggled in the ratings despite winning Emmy awards and garnering acclaim from fans, and since each half-hour episode features a new story and new actors the show features some memorable actors including Burgess Meredith, Jack Klugman, Agnes Moorehead, and William Shatner. Episodes like Time Enough At Last, To Serve Man, and Nightmare at 20,000 Feet”

These are not the only examples of great Twilight Zone episodes, but they also exist as some of the finest half-hour dramas that have ever aired on television. CBS canceled the show after its fifth season, but its effect on popular culture far surpassed even the wildest of expectations. The Twilight Zone is an institution of quality and stunning television, and unlike others, at its time it's one that producers and storytellers are still trying to recreate.

CBS has brought The Twilight Zone back many times in the 60 years since its debut, as well as the feature film in 1983 that adapted some memorable stories while bringing new stories into the fold for the big screen.

In under a decade, television ownership in the United States went from 20 to 90%. This potential for significant growth was evident, even in the early part of the 1950s. Recognising this, Columbia Broadcasting System split into two dedicated networks for television and radio, and directed to do everything possible to create their own distinct identities.

When CBS Television Network (CBS) debuted the first documentary series "See It Now"

and captured the broadcasting spotlight when it premiered "I Love Lucy" CBS President Frank Stanton saw an opportunity to capitalise on this new interest by introducing a new corporate identity. The responsibility for developing this fell to William Golden. Golden had started his career in the CBS Radio promotion department in 1937 and, by 1951, had worked his way up to creative director of advertising and sales promotion.

The introduction of a new logo intended to help separate CBS Network Television from the

CBS Radio Network, clearly differentiate the network from other television networks and was part of a broader effort to develop the overall impression of CBS as a place to see quality images. The now-iconic 'CBS Eye' was designed with the help of graphic artist Kurt Weihs, and was inspired by hex symbols drawn on Shaker barns to ward off evil spirits. Kurt Weihs later recalled that the eye was specifically influenced by a piece of Shaker art included in the article 'The Gift to Be Simple:

CBS has brought The Twilight Zone back many times in the 60 years since its debut. First, came the feature film in 1983 that adapted some memorable stories while bringing new stories into the fold for the big screen.

John Landis and Steven Spielberg were behind that endeavor, but the production was plagued with bad fortune and the movie didn't do enough to revitalize the brand.

Despite lackluster returns, CBS tried to bring the series back a few years later having decided that science fiction was a money maker in Hollywood, and the incarnation ran for 65 episodes and three seasons from 1985-1989. Twilight Zone went into hibernation again until 2002 when Forest Whitaker was tapped as the host, bringing back the Serling introductions that helped guide audiences into the other dimensions.

The series only ran a single year and the brand was put away once again. 2019 sees the series rebooted for a third time, this time with Monkeypaw Productions’ founder Jordan Peele (Get Out, Us, Nope) serving as both executive producer and host.

Twilight Zone now finds a home on the subscription service Paramont+ which may aio in its longevity better than if it had to survive based on ratings alone.

Twilight Zone has been instrumental in inspiring numerous TV series and movies over the years with science-fiction anthology series such as Amazing Stories and the Outer Limits (both of which we could spend another class lecture speaking on).

Some movies act as large-scale adaptations of classic episodes too including the Serling-penned Planet of the Apes and I Shot An Arrow Into The Air,

Poltergeist ("Little Girl Lost"),

The Truman Show ("Special Service")

and Us ("Mirror Image").

Television has transformed in the years since Twilight Zone aired six decades ago, but it still owes a lot to this classic series. Rod Serling imagined a television show that could both entertain audiences and engage them in social causes, and there is perhaps a no better use of the power of television.