Day 001: Zombies! Where does that term come from?

A zombie (Haitian French: zombi, Haitian Creole: zonbi) is a mythological undead corporeal revenant created through the reanimation of a corpse. Zombies are most commonly found in horror and fantasy genre works. The term comes from Haitian folklore, in which a zombie is a dead body reanimated through various methods, most commonly magic like voodoo. Modern media depictions of the reanimation of the dead often do not involve magic but, rather science-fictional methods such as carriers, radiation, mental diseases, vectors, pathogens, parasites, scientific accidents, etc.

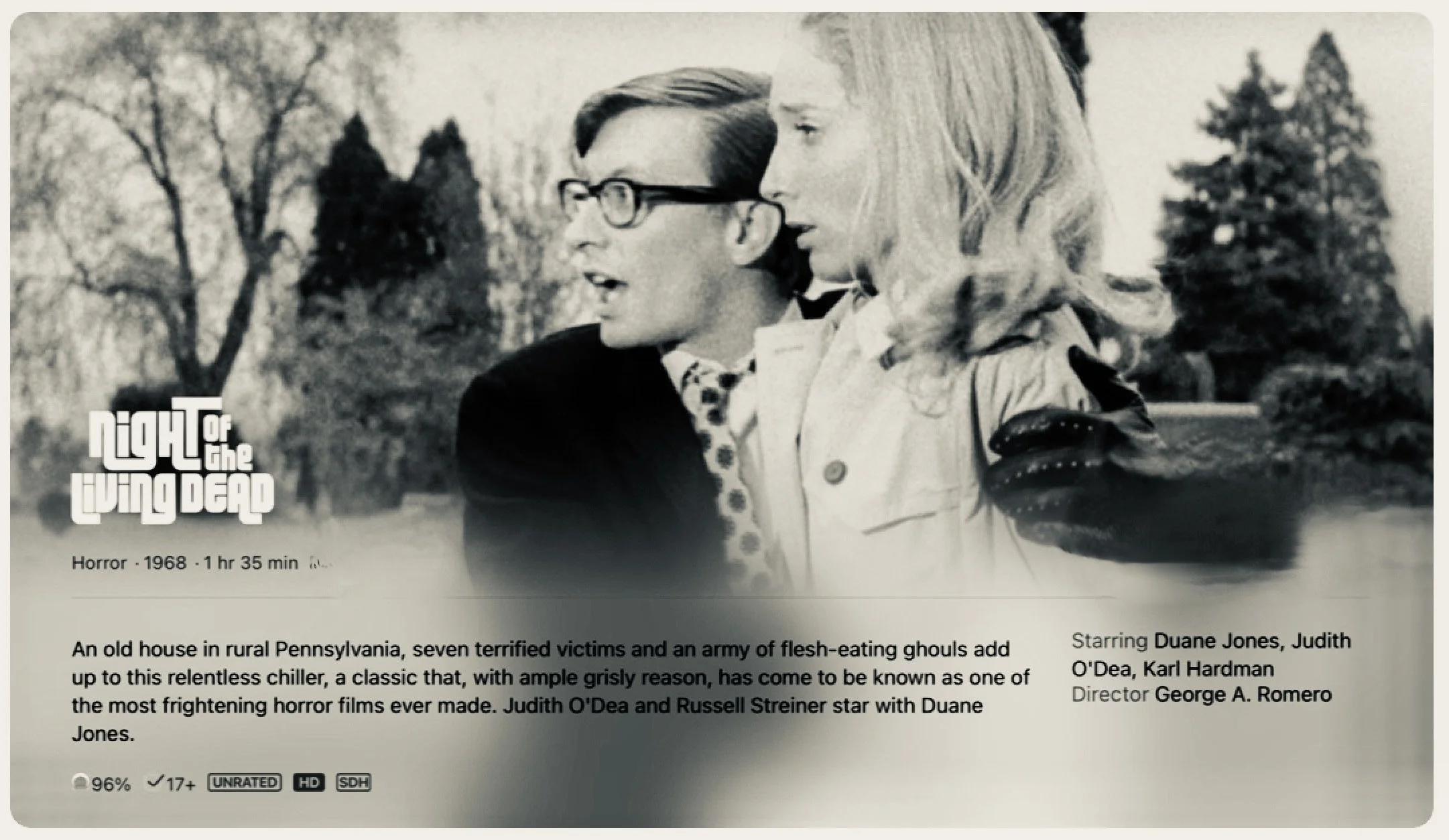

Shot outside Pittsburgh on a shoestring budget, by a band of filmmakers determined to make their mark, Night of the Living Dead, directed by horror master George A. Romero, is a great story of independent cinema: a midnight hit turned box-office smash that became one of the most influential films of all time. A deceptively simple tale of a group of strangers trapped in a farmhouse who find themselves fending off a horde of recently themselves fending off a horde of recently dead, flesh-eating ghouls, Romero's claustrophobic vision of a late-1960s America literally tearing itself apart rewrote the rules of the horror genre, combining gruesome gore with acute social commentary and quietly breaking ground by casting a Black actor (Duane Jones) in its lead role.

Night of the Living Dead was restored by the Museum of Modern Art and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the George Lucas Family Foundation and the Celeste Bartos Preservation Fund.

While there have been better-made horror movies in the 56 years since (some even directed by Romero himself), and there have been bigger budgets, better actors, and, more scares, there may not be any single denouement and message more frightening than the one George Romero leaves us with at the end of Night of the Living Dead. The word zombie is not used in Night of the Living Dead but, was applied later by fans.

Let's state for the record that zombies are rooted in black culture. Before Romero's creatures, which he considered "ghouls," zombies were undead slaves with roots in Haitian folklore and necromancy. The Afro-Haitian history of the zombi has largely been erased by popular culture with only a few zombie films, notably Wes Craven's The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988)

and, to a lesser extent, Lucio Fulci's Zombie (1979),

harkening back to the concept's roots. Although Romero had little control over the confluence of his ghouls with zombies, it seems fitting that a black character should take center stage in Night of the Living Dead, if not to reclaim the cultural association of zombies then at least to be given more of a presence and relevancy than a black character had ever had in the horror genre before.

Before, Night of the Living Dead, zombie films did utilize Haitian folklore in films like I Walked with a Zombie (1943) and the first zombie feature, White Zombie (1932).

But the culture surrounding these ideas existed in the background, as a kind of tribal magic that served as a tool for the wants and fears of "sophisticated" white people. In Victor Halperin's White Zombie, most black faces are seen in the background, undead slaves working a mill or providing cryptic, cowardly advice to the film's heroic white leads. As the title White Zombie suggests, the European image of the zombie served as the film's biggest selling point, even though the Haitian zombi and the sorcerer who controlled them, bokor, had never really gotten their day in the sun.

Although set in Haiti, White Zombie is a Gothic horror movie. Filmed on leftover sets from Universal's horror pictures, the film feels of that ilk though not as confidently directed or acted.

It's castles, coach drivers, butlers, and the love of wealthy white people caught in the corruption of black, no black magic. White Zombie is white. We learn about the history of zombies through Bela Lugosi's "Murder" Legendre, who is made up to look Asian, which is a whole other issue. But the film, which is good despite the obvious racial issues that are easy to point out in a modern context, creates a sense that not only are black people unable to tell their own horror stories, but they also are secondary to the stories of the white strangers who enter their lands.

Duane Jones, as the first black lead in the horror genre, is anything but secondary. Jones' image has carried the film's social message and become, perhaps unfairly, the surviving symbol of blackness in horror. This symbolism is equal parts because of the manner in which Jones handles the role and because the genre still has, in the 50 years since the release of Romero's film, struggled to offer heroic black leads.

Structurally, our introduction to Ben breaks format. We began our story with Barbara and Johnny and it would stand to reason that Barbara would become the film's lead. After all, we know why she's here, we have a sense of her backstory and familial connections. She is a known entity. But Ben comes from nowhere.

We know, by way of the monologue he delivers, how he ended up at the house, but not more than that. His story is a secondary narrative, a response to comfort the white woman in a catatonic state. But that changes once Ben takes charge and slaps Barbara, literally, out of her hysteria. A black man slapping a white woman feels shocking even now, but it 1968 it was unheard of. But Romero quickly establishes that Ben is a heroic figure, smart, capable and basically responsible for writing the guide on zombie survival.

Every aspect that horror had taught audiences about black men — that they are unimportant at best, and rapists of white women at worst — is tossed aside as it becomes clear that Night of the Living Dead is Ben's story rather than Barbara's. Even the shift from a graveyard to a modest house dispels the Gothic quality of the horror movie and replaces it with a residential horror. But that doesn't deter the film's capability to stir our deepest, or rather darkest, fears.

“all social norms break down when this event happens and a black man is caged up in a house with a white woman who is terrified. But you’re not sure how much she’s terrified at the monsters on the outside or this man on the inside who is now the hero.”

In an interview with the New York Times, Jordan Peele discussed Night of the Living Dead's influence on Get Out, saying, But Ben's heroism doesn't come easily or without pushback.

Barbara quickly falls to the background once the other occupants of the house, the Cooper family and teenage couple Tom and Judy, are introduced. Within the shelter house, a microcosm of American social relations is formed. The antagonism between Henry Cooper and Ben is immediate, as is their struggle for leadership. Henry acts as though his age and race predicate his leadership skills, despite the fact that he has been hiding out, while Ben boarded up the windows and doors, securing their safety.

It's difficult not to look at this through the lens of American slavery in which blacks were forced to build up this country on their backs while white people took the credit and the leadership role. It also seems worth mentioning that the Coopers are the only characters with a last name, which cements both their history and status — their legacy of whiteness.

While Henry Cooper's wife, Helen, doesn't agree with her husband, she remains largely passive, concerned solely with the fate of her infected daughter rather than the fate of strangers. Helen's position speaks to the complacency and lack of allyship seen from so many white women who would fight for their own rights but ignore the cries of blacks. Tom and Judy attempt to build the bridges of communication between Henry and Ben, and ultimately agree that Ben is a more sensible leader. These teenagers are the hope of the future, the change of the '60s that would see them move, if only slightly in some cases, away from the feet of their white ancestors and into the arms of revolution.

Even when Henry Cooper acquiesces and gives Ben leadership begrudgingly, his pride still prevents him from fully trusting the black man's survival skills. It's the cellar that he insists is the safest place and believes that the sanctuary's resources should follow him down there. This cellar, the Coopers' dwelling place, can be seen as the subbasement of America and its worst impulses. "The cellar is a death trap," Ben says rightfully, while foreshadowing his own tragic fate. "We've got a right. We've got a right," Henry yells before Ben retorts "Is this your house?" in what has to be considered the proto-mic drop. Ben follows this up by saying

"Get the hell down in the cellar. You can be the boss down there. I'm the boss up here." These are America's division lines — the North and South, and even when they reconcile briefly, the tension between the two parties proves to be their undoing and leads to the collapse of this chamber piece set society.

Further insight into the aspects of voodoo can be found throughout zombie films. In the twenty-first century, American popular culture increasingly makes visible the performance of African spirituality by black women. Disney’s Princess and the Frog and Pirates of the Caribbean franchise are two notable examples. The reliance on the black priestess of African-derived religion as an archetype, however, has a much longer history steeped in the colonial othering of Haitian Vodou and American imperialist fantasies about so-called ‘black magic’.

Within this cinematic study, Martin unravels how religious autonomy impacts the identity, function, and perception of Africana women in the American popular imagination. Martin interrogates seventy-five years of American film representations of black women engaged in conjure, hoodoo, obeah, or Voodoo to discern what happens when race, gender, and African spirituality collide.

As a component of this month's Thirty-One Night's lecture series, here's two top choice Zombie films that maybe or maybe not aren't on your radar. Enjoy!

Zombies' is a timely film. In the context of Extinction Rebellion, and the promise of a Green New Deal, there is growing fear over the correlation of climate breakdown and human extinction. Yet these actions, born out of novements in Europe and the United States of America, fall short of drawing connections between their own political systems and economies, and extractive, violent colonial histories that are complicit in creating the conditions for such crises to have arisen. They fail to acknowledge the long histories of extinction - threatened and enacted - to which black and brown bodies have been subjected, and the fierce resistance which already exists in our communities.

The New Economics Foundation invokes the language of militarisation in their programme towards a halcyon Green New future - 'a'carbon army' of workers to provide the human resources for a vast environmental reconstruction programme - and Extinction Rebellion's actions are already characterised by the violent exclusion and erasure of black and brown bodies and knowledge. It begs the question, when they speak of extinction, to which humans are they referring?

As ever, radical black excellence is on hand to elevate the discourse, and the Congolese-born Belgian artist Baloji's short film 'Zombies' acts as a tonic, providing us with a reflection on how people who have struggled against forces of extinction for centuries are not only crafting creative reconstructions of life, and relations between humans and the earth, but also performing and enacting those reconstruction in the present.

Rather naturally, Japanese movies have been far more interested in Hiroshima and Nagasaki than have Americans, but it is remarkable how little anger the films express toward the US. Only the 1953 Hiroshima, financed outside the studio system by the teacher's unions, really works up any fury about the use of the Bomb itself. Black Rain is no exception. While its recreation of the immediate aftermath of the bombing is often detailed and horrific, its real interest, as with Apart from Life is on the long term after-effects.

The focus on the most traditional of Japanese movie plots, the search for a good marriage for a nice young woman, personalizes the effects of the Bomb in a much greater way than would have been possible with long attention to the city itself. The only real anti-American sentiment one might notice is the ailing friend who asks: Why didn't they drop this on Tokyo where the leaders were, rather than on out-of-the way Hiroshima? The rest of the movie is devoted to the attempt to re-establish traditional life, perhaps misguided but nonetheless understandable. And in the countryside, it may have been thought possible; the only hint we get of the emerging new Japan is the daughter of a neighbor who has returned home from her nightclub in the city to hide from the yakuza, for a reason never detailed.

Because of the focus on village life (this approach was also taken in the film Godzilla Minus One (2023), which helps add narrative to the amazing effects that garnered it an Oscar,) and because Yasuko is such an obviously nice young woman for whom we automatically feel empathy, the movie is never a drag. We are shown rather than preached to, which makes the film not only more interesting but also more powerful. The result is a terrific, unforgettable movie.