Day 009: The Plug-in Drug: The Biology of B-Movie Monsters Biology and Geometry Collide!

Size has been one of the most popular themes in monster movies, especially those from my favorite era, the 1950s. The premise is invariably to take something out of its usual context--make people small or something else (gorillas, grasshoppers, amoebae, etc.) large-and then play with the consequences.

However, Hollywood's approach to the concept has been, from a biologist's perspective, hopelessly naive. Absolute size cannot be treated in isolation; size per se affects almost every aspect of an organism's biology. Indeed, every aspect of an organism's biology. Indeed, the effects of size on biology are sufficiently pervasive and the study of these effects sufficiently rich in biological insight that the field has earned a name of its own: "scaling."

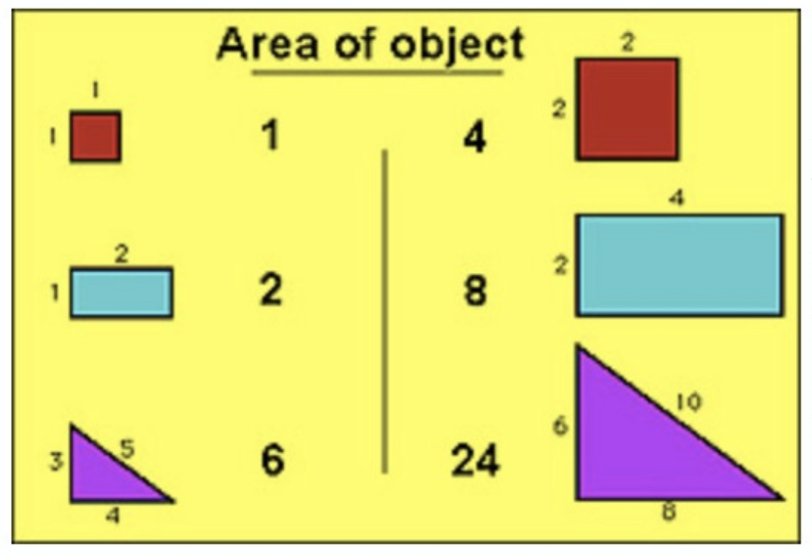

The conceptual foundations of scaling relationships lie in geometry. Take any object--a sphere, a cube, a humanoid shape. Such an object will have a number of geometric properties of which length, area, and volume are of the most immediate relevance.

The biological significance of these geometric facts lies in the observations that related aspects of an organism's biology often depend on different geometric aspects. Take physical forces.

If you change the size of this object but keep its shape (i.e., relative linear proportions) constant, something curious happens. Let's say that you increase the length by a factor of two.

Areas are proportional to length squared, but the new length is twice the old, so the new area is proportional to the square of twice the old length: i.e., the new area is not twice the old area, but four times the old area (2L x 2L).

Similarly, volumes are proportional to length cubed, so the new volume is not twice the old, but two cubed or eight times the old volume (2L × 2L X 2L). As "size" changes, volumes change faster than areas, and areas change faster than linear dimensions.

The magnitude of surface tension forces is proportional to the wetted perimeter (a length); a water strider needs long feet, not big feet, to skate on the surface of a pond.Adhesive forces are proportional to contact areas; geckos need broad, flat feet covered with millions of tiny setae to walk on the ceiling. Gravitational or inertial forces are proportional to volume (assuming that density is constant); a bird that flies into a window may break its neck, but a fly that flies into a window will bounce without injury.

The same dependence on different aspects of geometry holds for functional relationships.The forces that can be produced by a muscle or the strength of a bone are in each case proportional to their cross-sectional areas; the weight of an animal is proportional to its volume.

Physiological relationships are not exempt. The rate at which oxygen can be extracted from the air is proportional to the surface area of the lungs; the rate at which food is digested and absorbed to the surface area of the gut; the rate at which heat is lost to the surface area of the body: but the rate at which oxygen or food must be supplied or the rate at which heat is produced is proportional to the mass (i.e., volume) of the animal. If an animal performs well at any given size, size change alone implies that these related functions must change at different rates, since their underlying geometric bases change at different rates; if the animal is to be functional at the changed size, either functional relations must change or shape must change. Monster movies have extensively explored these scaling relationships, albeit usually incorrectly; knowing the true relationships often puts the entire movie into a new light.

Let's start small and work our way

At first glance, the spider seems to have the upper hand (or hands). But his reduced size gives the Incredible Shrinking Man a supercharged metabolism that makes him relatively quicker and stronger--as much as 70 times stronger--than he was at full

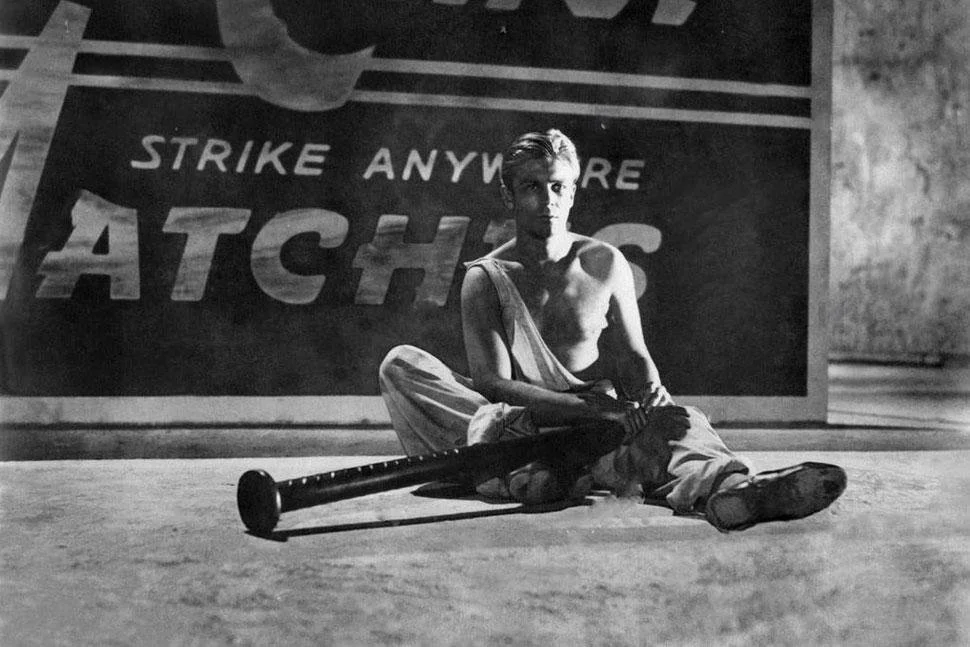

A world distorted beyond your imagination in The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) the hero is exposed to radioactive toxic waste and finds himself growing smaller and smaller.

He is lost to family and friends while fending off the household cat and must make his own way in a world grown monstrously large. He forages food from crumbs and drinks from puddles of condensation. In one famous scene, he defends himself against a house spider by using an abandoned sewing needle, which he has to struggle to lift.

When the Incredible Shrinking Man stops shrinking, he is about an inch tall, down by a factor of about 70 in linear dimensions. Thus, the surface area of his body, through which he loses heat, has decreased by a factor of 70 × 70 or about 5,000 times, but the mass of his body, which generates the heat, has decreased by 70 x 70 x 70 or 350,000 times. He's clearly going to have a hard time maintaining his body temperature (even though his clothes are now conveniently shrinking with him) unless his metabolic rate increases drastically.

Luckily, his lung area has only decreased by 5,000-fold, so he can get the relatively larger supply of oxygen he needs, but he's going to have to supply his body with much more fuel; like a shrew, he'll probably have to eat his own weight daily just to stay alive. He'll also have to give up sleeping and eat 24 hours a day or risk starving before he wakes up in the morning (unless he can learn the trick used by hummingbirds of lowering their body temperatures while they sleep).

Because of these relatively larger surface areas, he'll be losing water at a proportionally larger rate, so he'll have to drink a lot, too. We see him drink once in the movie--he dips his hand into a puddle and sips from his cupped palm.

The image is unremarkable and natural, but unfortunately wrong for his dimensions: at his size surface tension becomes a force comparable to gravity. More likely, he'd immerse his hand in the pool and withdraw it coated with a drop of water the size of his head. When he put his lips to the drop, the surface tension would force the drop down his throat whether or not he chooses to swallow.

As for the contest with the spider, the battle is indeed biased, but not the way the movie would have you believe. Certainly the spider has a wicked set of poison fangs and some advantage because it wears its skeleton on the outside, where it can function as armor. But our hero, because of his increased metabolic rate, will be bouncing around like a mouse on amphetamines. He wouldn't struggle to lift the sewing needle--he'd wield it like a rapier because his relative strength has increased about 70 fold. The forces that a muscle can produce are proportional to its cross-sectional area (length squared), while body mass is proportional to volume (length cubed).

The ratio of an animal's ability to generate force to its body mass scales approximately as 1/length; smaller animals are proportionally stronger. This geometric truth explains why an ant can famously life 50 times its body weight, while we can barely get the groceries up the stairs; were we the size of ants, we could lift 50 times our body weight, too. As for the Shrinking Man, pity the poor spider.

Stop the projector! Time for a little analysis.

This film is a great example of an ‘B-Movie’ when released that became an ‘a movie’. yes a B-Movie.

Oh, you don't know what a B-Movie is?

The 1950s were a big time in American history, and so it's fitting that it was the time when moviegoers were most likely to find huge creepy things walking around on their big screens. Not every film can be the Citizen Kane of its day. For every high-budget "A movie" that commands significant promotion and funding from its studio, there are piles of B movies that scratch and claw their way into existence without the benefit of things like "a budget" or "a script" in some cases. To compare them with A movies in terms of resources and immersiveness isn't a fair proposition. Instead, discerning film fans are able to simply appreciate them for what they are.

This classic guide to little-known films neglected by the film-criticism establishment features interviews with Herschell Gordon Lewis, Russ Meyer, Ray Dennis Steckler, Ted V. Mikels, Larry Cohen, and others who dared to make independent feature films their way, without bowing to a committee or focus group. This is an oblique how-to manual, covering everything from financing, distribution, lighting, camerawork and acting, to publicity, marketing and screenwriting. Would-be filmmakers as well as scholars will find much inspiration and enlightenment in this volume, which has been used in college film classes. In-depth interviews focus on philosophy, while anecdotes entertain as well as illuminate theory. Lists of recommended films, an A-Z directory, and quotations are also included. Purchase your copy here for additional enrichment.

Lecture Part II

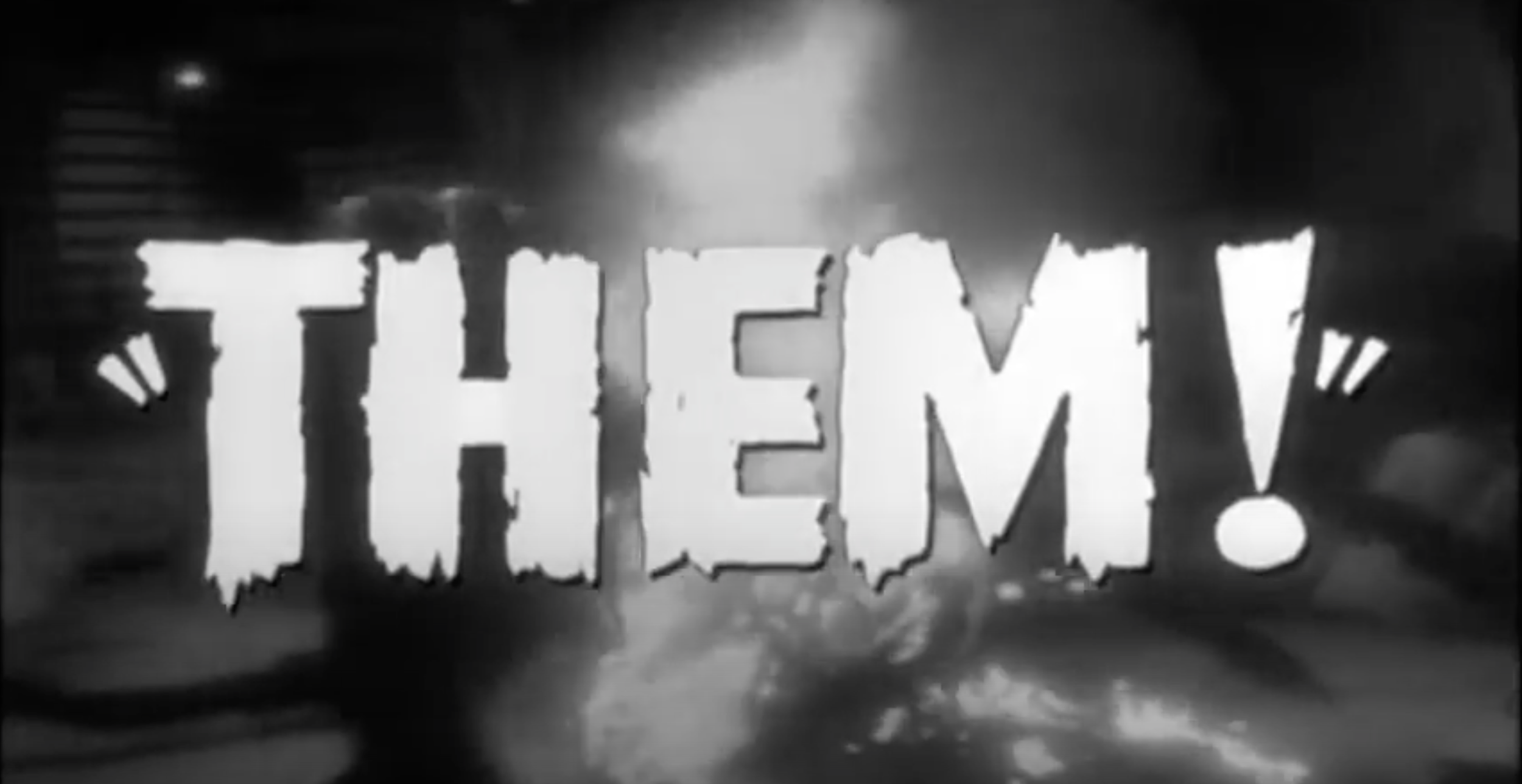

In one of the most intriguing openings in science fiction cinema, a little girl, wandering across the desert in a state of deep shock, is spotted by two New Mexico highway troopers who take her to safety. Nearby, they discover a trailer home that has been partially demolished by some unknown force and inside there is evidence of a bloody struggle. Later, when one of the police officers is gathering evidence at another site of destruction (a ransacked country store), he hears a strange, high pitched sound coming closer and closer until he's confronted with the horrifying source - the last thing he will ever see. Meanwhile, doctors try to jolt the little girl out of her catatonic state, finally succeeding with a formic acid sample, similar to traces found at the crime scene. The child becomes wildly agitated upon smelling the odor, screaming, "THEM! - THEM!", hence the title of the film which means GIANT ANTS!

A precursor to all the giant insect movies of the fifties, Them! (1954) was also one of the first science fiction thrillers to issue a warning about the dangers of nuclear testing and radioactivity in the aftermath of the atomic bomb's creation.

The film is truly unique in its conception - the first half is constructed like a detective thriller, the second half works as a fantasy adventure with the army and FBI agents invading the storm drains beneath Los Angeles where they hope to locate and destroy the queen ant's nest. Them! also has a welcome sense of humor that sometimes emerges during unexpected but appropriate moments, such as the sequence with the airline pilot (Fess Parker) who is being held for observation at a Brownsville, Texas, mental institution (No one believes his eyewitness account of the mutant ants). These comic touches are not surprising in light of director Gordon Douglas' earlier career: he got his start working for producer Hal Roach, directing Our Gang comedy shorts and Laurel and Hardy features like Saps at Sea (1940).

And when Douglas first read the script for Them!, he thought it would make an ideal vehicle for Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin!

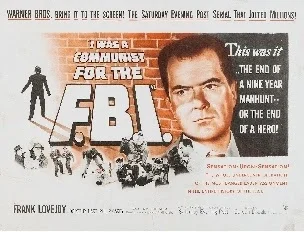

Luckily, Douglas didn't treat the film as a farce once production began and directed the film in the same terse, fast-paced style of Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950) and I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951), two first-rate crime thrillers he previously directed for Warner Brothers.

But if anyone deserves credit for the film's success, it's Ted Sherdeman, a former staff producer at Warner Bros. who was instrumental in developing the project. First, he commissioned the original story from George Worthing Yates, which appeared as a diary account about giant ants nesting in the New York subway. Sherdeman later told Steve Rubin of Cinefantastique magazine that "the idea appealed to me very much because, aside from man, ants are the only creatures in the world who plan and wage war, and nobody trusted the atomic bomb at that time." Yates was also hired to write the screenplay but his version proved to be cost prohibitive since it would have required far too many special effects sequences. Russell Hughes, a contract writer for Warners, was brought in for a rewrite and it was he who fashioned the narrative as a detective story that transitions into a chase thriller in the second half, culminating in a climax at the Santa Monica pier.

Unfortunately, Hughes died prematurely from a heart attack, completing only 20 pages of the script, but Sherdeman, undaunted, completed the screenplay himself, though he was forced to change the ending. The cost of renting the Santa Monica pier for one day was too expensive so the storm drains below Los Angeles became the setting for the film's finale.

This was actually a much better choice since the dank tunnels provided a much more eerie and claustrophobic atmosphere.

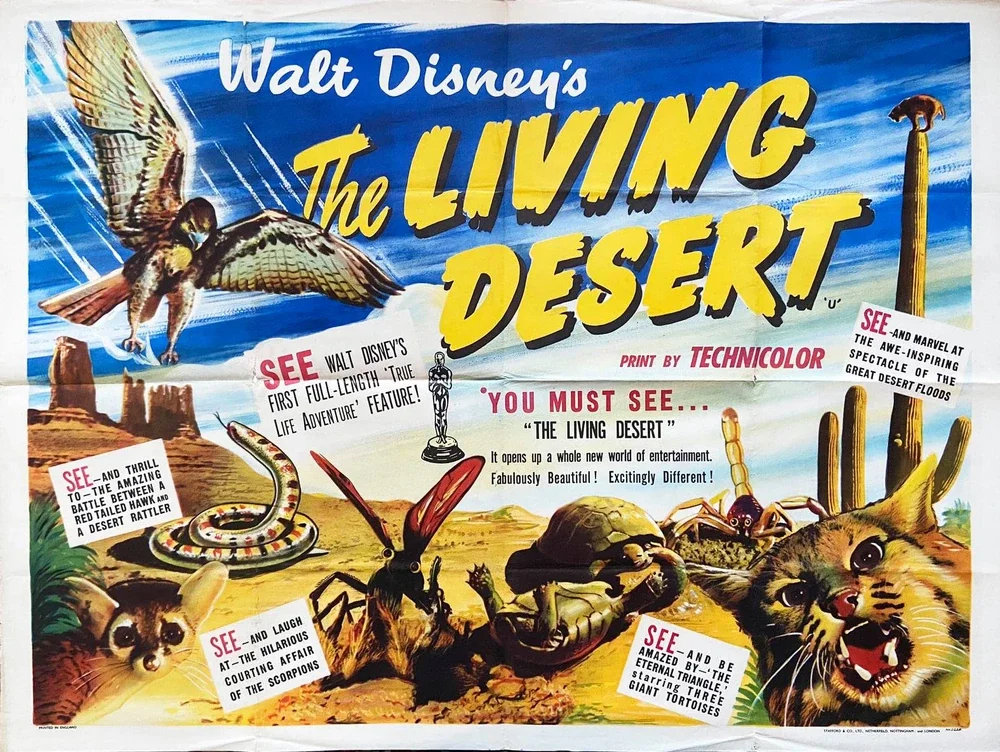

Sherdeman's next hurdle after the scripting was convincing his superiors to produce the movie. He tried to generate interest with drawings and a beautifully shot 16mm film about ants made by two UCLA entomologists (their footage would later be developed into a film for Walt Disney - The Living Desert (1953)

He even went to the trouble of having art designer Larry Meiggs create a three-foot ant head with movable antennae and mandibles which convinced WB executive Steve Trilling to shoot a film test. When studio mogul Jack L. Warner, who wasn't interested in making giant ant movies, saw the test footage, he knew he could sell the idea to a rival studio and offered it to 20th-Century-Fox.

As for the actual filming of Them!, Cinefantastique correspondent Steve Rubin wrote that "Two main ants were constructed, one fully, the other minus the hindquarters and mounted on a boom for mobility. Behind this, a whole crew, mounted on a dolly, manipulated the various knobs and levers that made the mechanical model come alive. Douglas laughed:

"You would have a shot where an ant comes into the picture and if you glanced back behind the creature you would see about 20 guys, all sweating like hell!" A number of "extra" ants were also constructed for scenes where large numbers of the creatures appeared, but where mobility was not essential. These ant models were equipped only with heads and antenna that would be activated by the force from the wind-machines used to whip up the sand storms required on the desert locations."

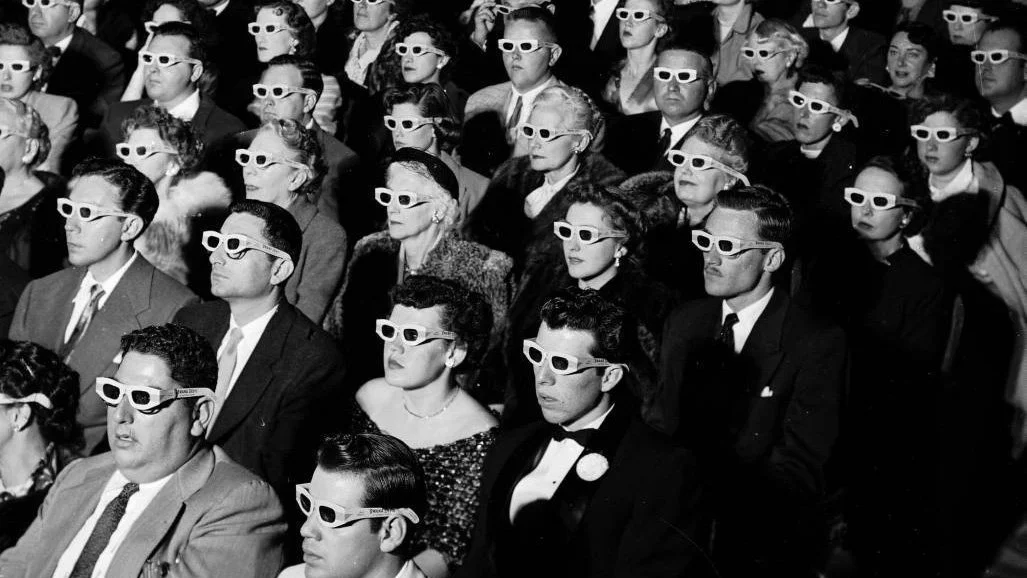

Them! had originally been conceived as a 3-D feature in color and the giant ants were given a purplish shade of green; their eyes were a soapy looking mixture of reds and blues that changed shades constantly and made them appear to be alive. Unfortunately, these effects were lost when Warner Brothers decided to release the film in black and white without the 3-D effect to save costs.

Nevertheless, the film still proved to be enormously successful when released, becoming one of the studio's top grossing films of the year and even receiving favorable reviews from critics who usually dismissed horror and sci-fi films. The New York Times review proclaimed Them! "one ominous view of a terrifyingly new world" and that "it is definitely a chiller...fascinating to watch." Jack Warner remained unconvinced, however, and told his staff after a screening, "Anyone who wants to make any more ant pictures will go to Republic!" Obviously, the studio mogul was a poor judge of science fiction films for Them! is among the best, a cautionary tale about the dangers of the atom bomb and a frightening view of nature run amok.