Day Two: EMBALMED Memoriam...

“Last night I was in the Kingdom of Shadows. If only you knew how strange it is to be there. It is a world without sound, without colour. Everything there - the earth, the trees, the people, the water and air - is dipped in monotonous grey. Grey rays of sun across the grey sky, grey eyes in grey faces, and the leaves of the tree are ashen grey. It is not life but its shadow, it is not motion but its soundless spectre. ”

When Dracula was reintroduced into critical debate in the 1970s it was largely due to the enthusiasm of psychoanalytic critics for the novel's evocative interpretations of unconscious fantasies of desire. Such analyses quickly widened into an intense interest in gender and sexuality, perceived both psychoanalytically and historically, that has tended to dominate critical opinion for over two decades. As early as 1984 Christopher Craft, in his influential essay on gender inversion, noted the pervasiveness of the focus on sexuality when he claimed that "modern critical accounts...almost universally agree that vampirism both expresses and distorts an original sexual energy".

By the 1990s it had become commonplace to signal this critical consensus, as exemplified in the work of Rebecca A. Pope and Elisabeth Bronfen, and even at times to challenge its superiority, as Stephen D. Arata did in his important reading of Dracula as a text grounded in colonial confrontations. More recently critics have expressed their disappointment in the limited range of critical approaches to Stoker's work. One of the leading scholars of Stoker's work, William Hughes, has argued that "modern criticism's preoccupation with sexuality dominates-and indeed inhibits the development of-the debate on vampirism. Hughes's expressed disappointment with the limitations of Stoker's criticism has been effective: since 2000 critical approaches to Dracula have been increasingly inventive and varied, adding greatly to our understanding of the novel's place within Irish literary history, Victorian popular culture, and modern technologies.

Nevertheless, one area of criticism that has still to re-emerge alongside these others is the historicizing of Dracula within the various scientific contexts that pervaded Victorian culture in the final decade of the century.

Bram Stoker's Dracula first appeared in the British literary marketplace in 1897, just in time to offer its own commentary on the state of the body in this new age of cinematography - understood broadly as the writing or reproduction of movement. The novel's contribution to cultural debates about the degeneration of the species, and Stoker's adoption of the scientific thought of such notable figures as Nordau, Charcot, and Cesare Lombroso, are well known by now. Yet, while there has always been an intimate correspondence between Dracula and the cinema, the novel's debt to fin-de siècle theories of the moving image have yet to be explored to their fullest potential.

This essay intends to offer some insight into the cultural affinities between the novel and the emergence of cinematography, or what Tom Gunning and others have referred to as the "culture of attractions" at the turn of the century.

The two excerpts quoted above will condition my reading of the novel, and as such, I will return to them frequently throughout the following pages. Briefly, at the outset, we start with the idea that Maxim Gorky's review of the early cinema and Jonathan Harker's encounter with the image-movement of Dracula's body are both kinds of primal scenes of the moving image.

The hysterics produced in both, whether feigned or truly symptomatic, are indicative of modern anxieties about the seductive dangers of cinematographic or moving bodies on screen or in the pages of late Victorian gothic fiction. Fundamentally, Stoker's Dracula emerges in 1897 as a cultural document profoundly preoccupied not so much with technologies of inscription, as many critics have argued, as with fin-de-siècle thought about the experiences of modern time and movement.

The cinematograph made its first "official" appearance in Paris in December of 1895, entering a marketplace that had become increasingly aware of the mass appeal of large-scale visual images, moving or otherwise.2 In the following pages, I interrogate some of the contradictions at the heart of the early cinema's supposed revolution in scientific analysis of the human form through a reading of Stoker's gothic tale of vampire bodies.

Gorky's review of the cinematograph above is one of the most eloquent of late-nineteenth-century responses to the flicker of images embodied by the cinema, even though we find in his account a profound uncertainty about the camera's reproduction of real life and its corresponding excess of signification. For Gorky, and indeed for many contemporary reviewers of the film programs offered by the Lumières, Thomas Edison, and other prominent Victorian filmmakers, the cinema reproduced images of bodies that seemed to be haunted by the supernatural, and this was the case often despite claims that the cinematographic eye was infallible and only capable of reproducing real life as it.

THE VAMPIRE FILM: AN INTRODUCTION

As Stephen D. Arata observes in his seminal essay on Dracula, "The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization," what marks the vampire in Stoker's vampire ur-text is his monstrous fecundity.

What Dracula does and aspires to do (much to the dismay of Stoker's "Crew of Light," to borrow from Christopher Craft) is to procreate, to create more vampires—a premise that has been elaborated upon to the point of absurdity in twentieth- and twenty-first-century vampire fiction and film (if everyone is a vampire, what's left to eat?). A hallmark of the vampire tradition in fiction and cinema is thus the anxiety of the living over the potential proliferation of the undead. But vampires seem to breed more vampires wherever they go. The viral potency of the undead is also evident, albeit in a (marginally) less threatening form, in the constantly expanding corpus of secondary literature on vampires in fact and fancy.

It appears that once academics get bit, they can not stop talking about vampires, and in the same way, vampires breed more vampires, and books on vampires seem to generate more books on vampires!

Four of the most recent entries in the category of undead scholarship:

David Keyworth's Troublesome Corpses: Vampires & Revenants from Antiquity to the Present

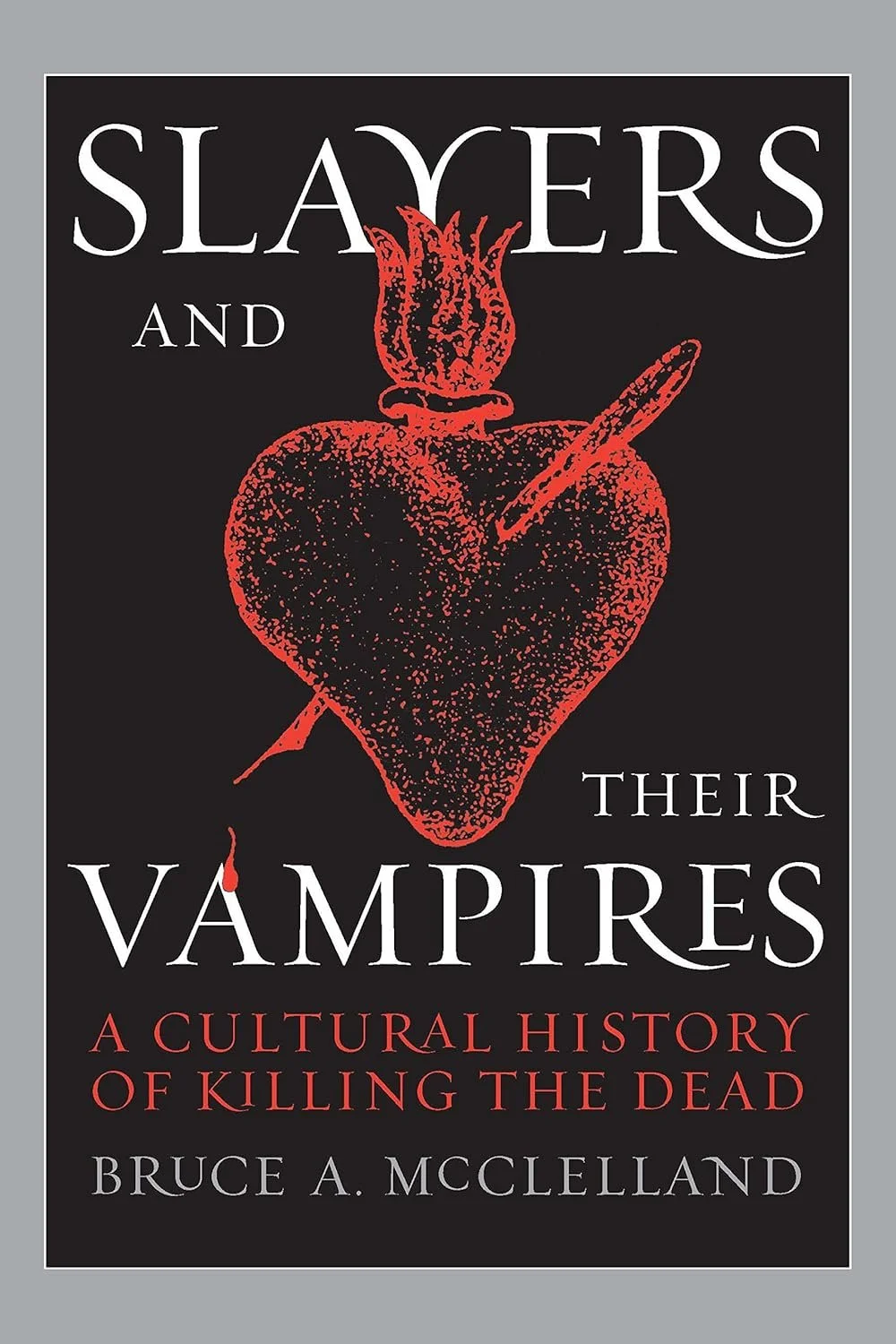

Bruce A.McClelland's Slayers and Their Vampires: A Cultural History of Killing the Dead

John S. Bak's Post/Modern Dracula: From Victorian Themes to Postmodern Praxis

Stacey Abbott's Celluloid Vampires: Life After Death in the Modern World

, demonstrate the scope and breadth of the vampire's icy grasp.

From ancient Greece to our modern moment and from medieval European folklore to contemporary cinema, these four books, taken together, offer a fascinating-if at times frustrating-overview of both the vampire's metamorphic abilities and its persistently hypnotic gaze. At the same time, this quartet of bitey books tells us quite a bit about our preoccupations and desires in the early years of the twenty-first century.

A QUICK DEFINITION FOR VAMPIRE FILMS INSIDE HORROR FILMS

A large and heterogeneous group of films that, via the representation of disturbing and dark subject matter, seek to elicit responses of fear, terror, disgust, shock, suspense, and, of course, horror from their viewers. Horror is a protean genre, spawning numerous sub-genres and hybrid variants: gothic horror, supernatural horror, monster movies, psychological horror, splatter films, slasher films, body horror, comedy horror, and postmodern horror....

Horror films present unpleasant experiences, but usually do so in a way that renders them pleasurable and safe: the fact that people seem to enjoy being frightened has given rise to work on and in tandem, cognitivism, phenomenology, and haptic visuality.

“I think it’s a very sumptuous, elegant, imaginative, strange project. I get a kick out of it because there were so many things we did that were chancy. We didn’t do the conservative thing, by any means. I like it when I get a chance to do that. Some things work better than others, and some people like some of the actors in it better than others.

But you make a lot of films, and they’re like your children—and, in fact, the ones that people like the least that are the ones that are your favorite.”

It could be deemed rather poetic that the origins of two of the most iconic and beloved horror movie creatures can be traced back to a single weekend in 1816 hosted by Lord Byron—both Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and John Polidori’s The Vampyre were the result of a writing challenge proposed by the poet himself, prompting his guests to come up with their own ghost stories. It was this undeniable power of the imagination manifesting itself as the written word that, ultimately, led to director Francis Ford Coppola falling in love with what would later become the world’s most popular vampire. It also made him realize the extent to which the blood-sucking Count is capable of both mesmerizing and terrifying audiences. The story goes as follows: when Coppola was 17, he worked as a drama camp counselor. His then-girlfriend had the same job but was working for a nearby affiliated camp. In order to get the 9-year-old campers to sleep so that he could go see her, the future filmmaker would read to them Irish author Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula in its entirety. Was the novel sleep-inducing? Hardly. But to Coppola, it seemed like a good idea at the time. For more enrichment on this topic consider reading the in detail essay by Koraljka Suton. entitled How Francis Ford Coppola Breathed New Life into ‘Bram Stoker’s Dracula’

As a component of this month's Thirty-One Night's lecture series, here's two top choice Vampire films that maybe or maybe not aren't on your radar. Enjoy!

The film is a remake of a classic, albeit an insufficiently familiar one: Bill Gunn's "Ganja & Hess," from 1973. It's a sort of horror film that's a psychedelic, incantatory fantasy about a black art collector (that's Hess) who comes into possession of an ancient Ashanti dagger and becomes a victim of its curse. Stabbed with the blade, he doesn't die but becomes addicted to blood. His first victim's wife (that's Ganja) shows up at his lavish rural estate; Ganja and Hess's romance and marriage is centered on their now shared quest for blood, even as Hess maintains another hemophage life on the down-low.

Lee reprises the entire narrative progression of "Ganja & Hess," as well as the characters from Gunn's film, most of the details of the story, and even chunks of its dialogue. Nonetheless, he makes the movie entirely his own, by way of his specific directorial qualities-in particular, elegance and intensity.

Lee's stylistic elegance shows the outward signs of grace and taste that arise from money.

His smooth and luminous wide-screen images conjure ease, scarcity, excess, a fullness of style that suggests there's lots more where that came from-Baudelaire's "luxury, calm, and voluptuousness" brought to the screen. It's an elegance that arises from craft, too-the craftsmanship of the furnishings and the objets d'art that fill Hess's exquisite seaside villa on Martha's Vineyard.

Just as the action in Park Chan-wook's Thirst is getting under way, Tae-ju (Kim Ok-vin) challenges Sang-hyun, the young Catholic priest she's just started fucking, to prove that he's really a vampire. Sweeping her up in his arms, he leaps from the rooftop of the high building where they've met up; though they float down safely, she's soaring, dizzy at the prospect of hanging with a vampire and even becoming one herself. From this point on, it's Kim Ok-vin's movie. Guilt-ridden, Sang-hyun is sure they are both going to hell; but since she's not a believer, she's determined to bleed vampiredom for all its worth. Right up to the inevitable, and nicely conceived, ending, her fun makes a mockery of mort)ality.

The intro shows Sang-hyun (played by Song Kang-ho, star of the blockbuster The Host) giving himself to Jesus by volunteering to be injected with a trial vaccine for a disease that causes the skin to erupt in boils followed by internal bleeding and a grotesque death. The disease kills him, but unlike the other guinea pigs, he comes back to life. The rub, though, is that one of the transfusions he had has turned him into a vampire, and only fresh blood can stop the return of the boils. Some of it he gets by supping at the transfusion tube of a comatose patient in the clinic where he ministers, but most comes from the family of a childhood friend he's called in to save: Tae-ju, her idiot husband, his mother, and various friends who come by to play mahjong, including a Filipina mail-order bride.

A GLIMPSE OF ANIME HISTORY: VAMPIRE HUNTER D

Vampire Hunter D is credited as one of the earliest anime productions targeted explicitly at the male teenager/adult demographic in lieu of family audiences, and capitalized on the emerging OVA market due to its violent content and influence from European horror mythology (such as the films of British film studio Hammer Film Productions). The film's limited budget made its technical quality comparable to most anime television series and other OVAs, but not with most theatrical animated films.

During the film's production, director Toyoo Ashida stated that his intention for the film was to create an OVA that people who had been tired from studying or working hard would enjoy watching, instead of watching something that would make them "feel even more tired".

It’s long been said that the 80’s were the golden age of anime. With rose tinted glasses, and fond memories of simpler days, many anime fans were introduced to the medium thanks to the masterpieces of this decade. Every now and then, we should take a step back in time to appreciate these gems.

Vampire Hunter D, is one of these long buried diamonds. This is not a review of the movie that came out in 1985, this is just a glimpse and a few thoughts about it and it’s impact forty years later.

This movie deserves to be mentioned because in this day and age, older anime falls off the radar. It can be easy to forget about them. Vampire Hunter D was considered a fairly huge success upon release. It mixed the finer arts of sci-fi and high fantasy in an easily digestible way.

The 1985 film carries a narrative that you can easily enjoy, without requiring knowledge of the series. The movie will explain things as it goes along.

The anime movie swiftly became known as a cult classic following its release, and that’s one of the many reasons it remains beloved to this day. In spite of it’s age, the anime holds up very well, all things considered. As one of the anime films to hit the United States in the ’90s, american fans were given a world that was little dark, and somewhat gritty.

All of this was wrapped in stunning visuals that only occasionally dropped in quality. It was the era of hand drawn, so occasional dips were to be expected. These visuals coupled with musical genius, making for an atmosphere that still echoes into fandom to this day.